| Learning by Heart: Creating Accountability through Community |

| at East Side Community School |

by Kathleen Cushman ____

|

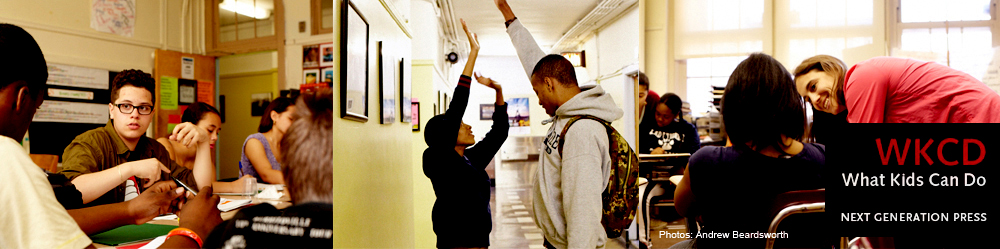

NEW YORK, NY — School had only been in session for eleven days on the bright September morning in 2012 when Mark Federman, the principal of East Side Community School, got the call from a New York City Department of Education official: Get everyone out of your building, and get them out fast. An alert custodian had noticed that the brick facade of the 90-year-old five-story school building in Manhattan’s Lower East Side neighborhood was pulling away from its steel structure and threatening collapse. Without a moment to prepare, Mr. Federman and his staff had to evacuate their 650 students in grades 6 through 12, sending them to makeshift shared quarters in widely separated neighborhoods. One year later, that difficult five-month exile had become the stuff of legend in this close-knit school community, which reflects the diverse population of its historically immigrant neighborhood. The high school served its displacement time in “a school of permanent metal detectors,” recalled Joanna Dolgin, who teaches eleventh-grade English. Walking into its windowless spaces, “the students had to take off their belts, their shoes, their hair pins, just to come to school. They had to pay a dollar to store their cell phones in a truck. The security guards often were angry with them for not being fast enough.”

When the scattered groups finally returned to their building, everyone seemed to second that emotion. “You can take us out of East Side,” reads the message stenciled by the graduating class of 2013 on the wall outside the school’s main office, “but you can’t take East Side out of us.” The unwavering foundation of committed community that East Side laid at its 1992 founding (by veteran educator Jill Herman) has grown steadily since. Held together by the mortar of mutual respect, the community culture in “this crumbling building”—as one veteran teacher laughingly concluded—“exudes love and care and academic excellence and creativity. It’s really hard to be in this space and not get caught up in the fervor of positivity." |

|

|

|

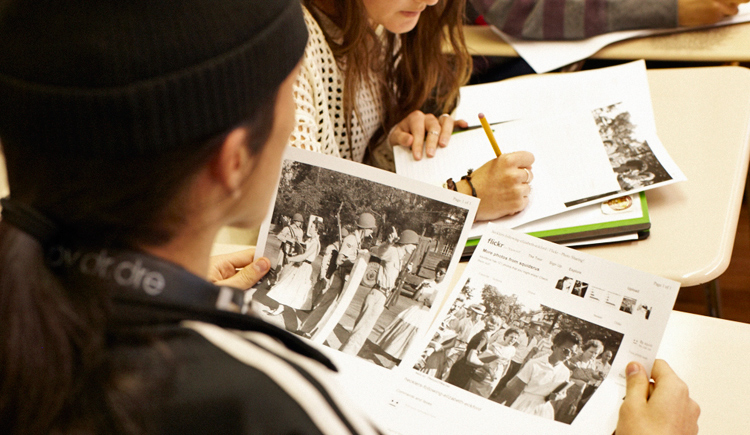

Making learning public Not just in behavior norms but also in the academic realm, accountability at East Side marries with a deep sense of community. At the end of every semester, when students in most New York City high schools are taking the state Regents exams, their East Side peers instead present and defend their work at “roundtables” for teachers and outside evaluators. In his welcome memo to guests, principal Mark Federman describes the high stakes involved:

The regularity of these twice-yearly roundtable rituals—six in each core subject by the time they reach senior year—means that East Side students get continual practice in oral and written reflection on their own work and in answering questions about the work from the larger community. For presentations by ninth through eleventh graders, each visitor sits with two students in a room where simultaneous roundtables are taking place. The culminating performance-based assessments of senior year, however, follow the model of a dissertation defense: a private session with two or three adults who have prior access to the work and enter into deeper discussion and feedback. A few weeks before presenting at her roundtable to fulfill the graduation requirement in science, an eleventh grader named Tanazia was in Erica Ring’s classroom, intently charting the growth of plants nourished by three differe In large part, teacher Ben Wides suggested, such academic depth results from the social and emotional supports that surround students from the time they enter East Side. As teachers show that they care about the wellbeing of their charges, they are also “letting kids know that we’re taking them seriously intellectually,” he said: “giving them rich and challenging questions to think about” and taking an interest in their ideas. When seniors arrive in his class, Ben Wides said, and choose a topic for the major history research paper they must defend for the graduation portfolio, they often pick an issue of personal interest. But he feels even greater satisfaction when he sees students “learning for learning’s sake—looking at a real question, engaging in intellectual inquiry on a topic that does not relate personally to them. That’s the essence. And the fact that they're constructing it for themselves, I think, is really powerful.” “Having their voice heard, being able to speak their mind,” said tenth-grade history teacher Yolanda Betances, “that becomes part of the culture in all of their classes, I think.” In the process, she added, “they also have a sense of developing and growing as young people—of how to interact with not only fellow students but people visiting the school. They’re part of a community.”

PHOTOS: ANDREW BEARDSWORTH This article is an excerpt from WKCD's full case study of East Side Community School, one of five schools featured in Learning by Heart: Five American High Schools Where Social and Emotional Learning Are Core. It was conducted by WKCD's research arm, the Center for Youth Voice in Policy and Practice. DOWNLOAD THE FULL CASE STUDY, "Developing Agency Through Community: East Side Community School" |

Students sharply felt the contrast with East Side, where “every casual hallway interaction reminds our kids that they’re part of a community, surrounded by adults who support and care about them,” Ms. Dolgin said. Even the relocated teachers felt isolated and unmoored, she added: “It really reminded me that even the work I do in my classroom is possible because of this larger community that we’ve created.”

Students sharply felt the contrast with East Side, where “every casual hallway interaction reminds our kids that they’re part of a community, surrounded by adults who support and care about them,” Ms. Dolgin said. Even the relocated teachers felt isolated and unmoored, she added: “It really reminded me that even the work I do in my classroom is possible because of this larger community that we’ve created.”

open-campus lunch policy as an example. “There’re so many distractions out there!” he exclaimed. “I can go bowling, go to the pier, do anything pretty much during lunch.” Yet “since the school has built such a stable environment,” he said, “we trust ourselves to come back to school. We’re willing to do whatever it is that we have to do.”

open-campus lunch policy as an example. “There’re so many distractions out there!” he exclaimed. “I can go bowling, go to the pier, do anything pretty much during lunch.” Yet “since the school has built such a stable environment,” he said, “we trust ourselves to come back to school. We’re willing to do whatever it is that we have to do.”