CLOSE-UP

Learning by Heart: Restorative Practices at Fenger High School

by Barbara Cervone, Ed.D. ____

|

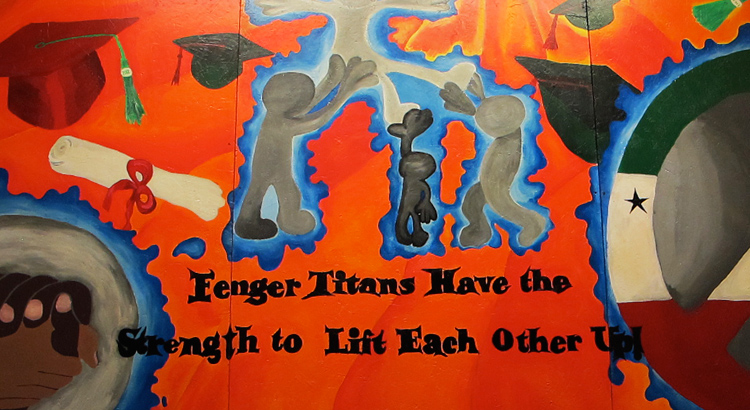

CHICAGO, IL —The stresses of being a teen in one of the Chicago’s most violent neighborhoods don’t trigger the metal detectors at the entrance to Fenger High School on the city’s South Side. But they can erupt quickly in the classrooms and halls of this “turnaround” school, where small transformations separate hope from heartbreak. Soft-spoken but tough, Shoshanna thought her teacher in senior English class was disrespecting her. She had called out to her teacher, who was helping some other students, but the teacher didn’t respond. Maybe it was because Shoshanna hadn’t raised her hand, like she was supposed to, or because her low-speaking voice was impossible to hear over the classroom din. Shoshanna got mad, got up, and walked toward the door. “What's going on?” the teacher asked. “I been trying to call you. I need you to come here!” Shoshanna shot back. “Whoa. Come on. Step outside,” the teacher said. Shoshanna complied, but she had already reached a 10 on the anger scale, and nothing the teacher said could stop her from feeling wronged. Her shouting soon drew a nearby security guard—at Fenger security receives special training in de-escalating students—but Shoshanna was on fire. She dropped the F-bomb and landed in the dean’s office. When the dean asked, “What's up?,” Shoshanna looked down, fell silent, then explained that she was pregnant and had a lot on her mind. In a school where zero tolerance policies ruled, Shoshanna would probably have been suspended, regardless of what had shortened her fuse. At Fenger, the dean decided this was a matter best resolved through peer jury, which has become part of the school’s nerve center. Within an hour Shoshanna, two of her peers, and her teacher were sitting down and sorting out what had happened and how Shoshanna could have handled matters differently (including raising her hand). Hard feelings eased, the group helped Shoshanna master the skill of making a genuine apology, a step she was now eager to take and did. Fifty-two days shy of graduation, Shoshanna had regained her place in the commencement line and learned a few lessons in what Fenger’s peer jurors call “positivity.” |

|

|

|

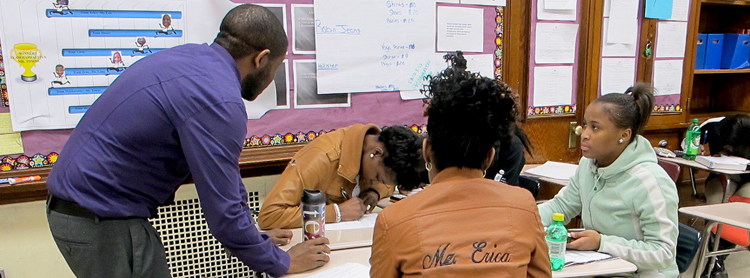

Social and emotional safety “Can I catch a nap?” a lanky, bleary-eyed youth asked, sticking his head into the office of Fenger’s school psychologist, Alejandra Argerich. “Of course,” Argerich said, rising to show him into a small, secluded room a few steps away. “Just check in with me before you go back to class.” It wasn’t the first time this young man had sought the quiet and safety of the school’s mental health quarters, Argerich explained. Where he lives, domestic violence often rocks the night; some days he just can’t stay awake in class. “It is better that he come here and replenish for an hour than struggle through the whole day, exhausted.” At Fenger High School, restorative practices go beyond embracing positive alternatives to zero tolerance, however vital these are to creating a culture of calm. In a community where poverty and violence have made harm and loss a norm, helping students feel safe has a profound psychological component. Asked what they like best about Fenger, students point to that deep support system and the sense of an arm always around them. Vada, a senior on her way to college, explained:

Developing such trust and connections—often when they have been badly broken—stands at the heart of the work by Argerich and her colleagues (two social workers and five counselors). A local headline framed it as a “public health approach to violence,” when the federal government granted Fenger an emergency $500,000 after student Derrion Albert famously met his death when gang violence overtook him on his walk home from school in 2009. Triage Hiring in-school mental health clinicians has been central to this approach. However, social and emotional triage at Fenger begins in the classroom. Teachers do the best they can to engage students for whom anger, depression, and isolation leaves them chronically on edge or underwater. Sometimes the triage starts in the halls. When anger or conflict reaches a tipping point, the school’s security guards, trained in de-escalating student emotions when they become raw, are the first to respond. “The students who are hurtin’ and quiet, they don’t come up on my radar screen,” said Keith Connor, head of security at Femger. ”The ones that are hurtin’ and angry, we know them pretty well.” During passing between classes, the dean keeps an eye out for students who are on edge and engages them in conversation so that he can take their emotional temperature. At weekly meetings, the school's CARE team reviews the cases of individual students, identifying those who m The philosophy that guides Fenger’s mental health work with students is straightforward. “We will reach out to you,” said Argerich. “We’re not going to tell you what to do, but we’re going to try to help you find out what you need and go from there. You’re going to teach us things and we’re going to do the same for you.” For its anger therapy groups, Fenger’s mental health staff relies on the evidence-based Think First program. For trauma, it calls upon the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) program. CBITS uses cognitive-behavioral techniques (e.g., social problem solving and cognitive restructuring) to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and behavioral problems in adolescents. Many students, such as those who suffer a death in the family, struggle emotionally yet do not fit the anger or trauma group profile. A coping skills group helps them get past their reluctance to share their feelings, using a curriculum the schoool's social worker tailored to match the needs of older and younger students. Whatever the group, the goals are the same, Argerich said. "We help kids gather their own resources, to find the protective factors they may have but don’t know they have—along with the ones they need to learn. And we try to build with them a network of support, here at the school, with friends, with a teacher. " It is patient work, done in regular consultation with Fenger faculty and students’ families. When students reach the end of one of the 12- to 15-week groups, they sometimes join the next. The clinical staff is on call as students individually check in at least once a week, whether they have “finalized” a group or not. “I’m not going to say it works every time,” Argerich continued:

|

|

Every adult who works at Fenger will tell you that simply listening to students is one of the most powerful tools they have. When peace circles and peer juries—and the formalized listening they demand—are not “in session,” students regularly knock on Robert Spicer’s door. “Do you have a minute?” they ask, and unravel what’s on their mind. Teaching students relaxation techniques offers an additional tool. Already, some kids drop in to meditate, write in a journal, or listen to music when it’s a rough day, Argerich said. “At this school, they go all out around the student’s emotions. They ask, they listen,” said Jamiesha. “Me, I feel comfortable here. I don’t wake up and think, ‘Oh I hope this don’t happen. I hope that don’t happen.’ You go in with an open mind and a clear mind and you think like, ‘I’m okay. I’m fine. I’m ready to learn.’”

This article is an excerpt from WKCD's case study of Fenger High School, one of five schools featured in Learning by Heart: Five American High Schools Where Social and Emotional Learning Are Core. It was conducted by WKCD's research arm, the Center for Youth Voice in Policy and Practice. DOWNLOAD THE FULL CASE STUDY, "They Never Give Up: Fenger High School, Chicago, Illinois" Note: Fenger High School began the 2013-2014 school year minus the additional $1.6 million in federal support it had enjoyed the year before. Its three-year federal school improvement grant had ended the previous June, a few months after WKCD visited Fenger. Few doubted that the infusion of additional money, and the staff and resources they bought, had made a dramatic difference at Fenger—that the school had turned around, though there certainly was more to do. Impact was not the issue. The issue was simple: the federal funds ran their course and the local well was dry. |

ight benefit from group therapy and other intensive supports. Often, students seek out that help on their own, an informal indicator of the emotional safety they are feeling. “It tells us how we’re doing planting trust,” said Tosha Jackson, the assistant principal who supervises the CARE team.

ight benefit from group therapy and other intensive supports. Often, students seek out that help on their own, an informal indicator of the emotional safety they are feeling. “It tells us how we’re doing planting trust,” said Tosha Jackson, the assistant principal who supervises the CARE team.