Learning by Heart: Soccer as Unifier at Oakland International High School

by Kathleen Cushman ____

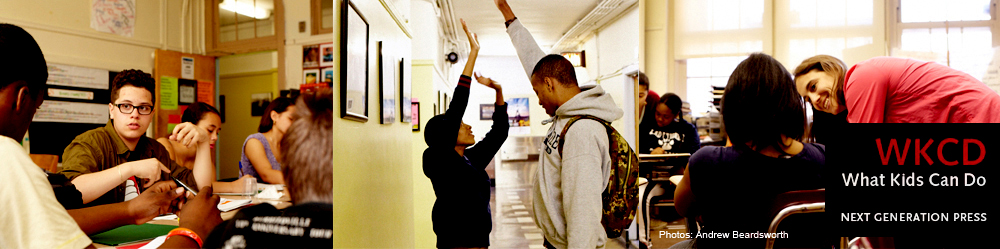

OAKLAND, CA — If you are a new student at Oakland International High School, there comes a point—after the district has tested your low English level, after your intake interview, after your long journey by city bus to the low-slung school building in the Temescal neighborhood—when you will find yourself alone and afraid in the Tower of Babel. Maybe, like Mical, you can catch at least some of what people are saying. After fleeing Eritrea through Sudan, she spent six months in a displaced persons camp in Texas, where she picked up some Spanish but little English. Now she lives in Oakland with an older sister, working at Burger King to help with her keep. Her father died four years ago; for six years she has not seen or spoken with her mother in Eritrea, though she keeps hoping to find her somehow. When she started ninth grade at Oakland International four years ago, the weight of all she carried kept her silent. “Some people, they just get shy and they don’t want to talk to other people,” Mical said, remembering that anxious time. “I know how it feels . . . maybe they won’t like me.” Since its 2007 founding, Oakland International has been a point of entry into the city's schools for the newest of its teen-age immigrants, who come here from more than 30 countries and speak at least that many languages. Fully a third of the 330 students here are refugees from war-torn countries, and 25 percent come with little or no formal education. Yet in the midst of their frustrating transition to a new language and culture, these young people are finding common ground and motivation to learn on the soccer field. With its cross-cultural appeal—played in over 200 countries by anyone with access to a ball, a patch of land, and a few sticks for goalposts—soccer has provided an ideal way for them to forge social and emotional bonds at the same time that they practice their new language. An open door to inclusive play Early in the school’s history, a partnership with the nonprofit Soccer Without Borders sprang from the teaching of soccer in physical education class. Led by Ben Gucciardi, it grew like wildfire; roughly a third of all students here now take part, playing on various teams that compete in Oakland and its surrounds. However, the program goes far beyond athletic competition. It encompasses youth development and leadership as well as academic monitoring, intervention, and support. “My soccer program, they always support me, everywhere,” said Ravis, a student from Democratic Republic of the Congo. “My personal life, on the field, acade First priority, Mr. Gucciardi emphasized, goes to establishing an open-door culture of inclusion and acceptance. “Regardless of language, culture, ethnic identity, gender, sexual orientation, skill level, whatever—in this space everybody can get out there and just be themselves, and get encouragement and positive reinforcement,” he said. “It’s okay to be competitive,” he added, cheerfully acknowledging the rivalries of older adolescent boys in particular. Unlike the boys who take part in the program, for cultural reasons almost none of the girls at Oakland International have played soccer before. Leya, an older student from Eritrea who had recently enrolled at the school, stepped onto the field in boots one afternoon at the invitation of some other girls. Before long, she was happily lacing on some athletic shoes from the storage locker and encouraging a younger girl from her country to join the fun despite her father’s disapproval. (“It’s just exercises,” others coaxed, to no avail.) Simply to enjoy “silly, goofy, physical fun” out on the playing field, noted Mr. Gucciardi, “is such a leap in terms of societal gender roles” for many young women. Katie Nagy, one of two female coaches for the program’s girls teams, agreed. “It takes some convincing,” she said. “We talk to their families and provide a different perspective on what the sport can do for their daughters in life.” |

|

Creating bonds of mutual support By bringing together peers who may not otherwise meet in academic classes, students made clear, the soccer program expands their social network. “If we see each other outside practice, we say hi to each other and ask about how the classes are going,” Helen said. Playing together also deepens their sense of emotional safety. “We’ve got to know each other here,” said Emory. “We don’t fight. We are like a team, a family, and we feel safe.” Such cross-cultural friendships are the program’s most important outcome, Ben Gucciardi believes. For many students, he said, “the first time they build relationships outside of their language group is on the soccer field.” He told of an Arabic speaker in tenth grade:

Omar, who comes from Colombia, regards Mr. Gucciardi as “my second father,” he said. “For him it doesn’t matter the skills that you have. He is always substituting the people and make everybody play equal amount of time. No matter if we win or lose, for him what matters is that we have fun.” Ravis, who captained one of the boys teams, agreed emphatically. “That’s why whenever we play I give everything I have,” he said. “Even though we lost, I’m still smiling. Play as hard as you can, try anything as hard as you want to try, but don’t forget that we always play for fun. That’s the spirit that keeps me going and loving the team that I’m in. Their soccer coaches also serve as confidants and advisers, many students said. “If this man’s going to tell you what you did wrong,” said Ravis, “it’s like, ‘I’m mad at you. Don’t do this anymore. Try to change.’ I like people who tell me the truth: how I did good, how I did bad, how I need to improve.” Many of her female players, Ms. Nagy observed, participate less for the program’s athletic or competitive aspects than for its family-like environment. “When I play soccer, it feels like a second home,” said Rebekah, a student from Malaysia. “They feel like my real family, and we respect each other.” Helen confides in her teammates or coaches when personal problems arise for her. “They’re really nice,” she said. “I can just talk to them about everything.” In her first year of coaching, Ms. Nagy has observed the effects of the trust her players develop in each other. Despite their very different skill levels, “they find a common ground on the field with a soccer ball,” she added.

|

|

Developing leadership With the young men in the program, Mr. Gucciardi sees a variation on that theme. “The male ego gets bruised when they can’t speak English,” he has noticed:

Behavior change, he remarked, takes place gradually. “It starts with some positive reinforcement when they do the right thing,” he said:

The relationships among teammates and coaches reverberate in other contexts as well. In one memorable incident, a bad fight over a girl broke out between two boys from different language groups, sparking a dramatic face-off between their Arabic-speaking and Spanish-speaking supporters. At soccer practice later, the players (many of them boys from the same two language groups) decided to take a stand to calm the waters. Forty-five minutes before school started the next day, some twenty male and female teammates stood together in its entryway and greeted their peers, holding signs in many languages: “We want peace in our school.” At such moments, said Mr. Gucciardi, the Soccer Without Borders program “becomes much more than the sport itself.” By stepping up to facilitate healing in that crisis, students showed the leadership and values that it stands for. “We all like soccer,” the coach said. “But we’re using it as a platform, a means, a vehicle for building community.” |

|

Learning language through (e)motion Creating that community has had its own remarkable effect, which goes directly to the central mission of the school: helping its language learners to communicate successfully in English. “One of our rules is to do your best to speak English on the field,” said Ben Gucciardi. “And I think that really helps. There are certain times when they are just forced to speak English in order to communicate with teammates from different language groups. There’s no other way.” The research on acquiring and remembering language has long linked action with words: we remember phrases like “throw me the ball” better, for example, if we are actually tossing a ball than if we study it in a textbook. More recently, cognitive scientists have theorized that thought, memory, and language derive from actual motor and sensory experience. According to this view, what we know and how we reason—whether we are kicking a ball into a goal or curled up with a good book—depends on activity in the same neural systems used for perception, action, and emotion. This understanding has important implications for how English language learners in high school enter academic discourse and come to conceptual understanding of abstract phenomena. The young soccer players on the fields behind Oakland International provide a rich picture of English language proficiency progressing (quite literally) by leaps and bounds. Caught up in the physical and emotional flow of the game, they let go of their fears and call out to each other freely, reinforcing with every play their growing understanding of meaning in their new language. “On the soccer field it was like I was in another world,” said Ravis. “Everything they would tell me, it would just get in my head—I was like, ohh!” Helen, from the girls team, agreed with him. “It’s more free outside,” she explained:

“It’s so awesome,” said Isis, a student from Mexico. “People don’t know how to speak English, so we speak our own language sometimes, and sometimes we speak English, but we can still understand each other through soccer." |

|

Supporting athletes as students Coach Gucciardi has begun exploring ways to intentionally integrate academic vocabulary—such as “evidence” and “analysis”—into the language of soccer practice. In the meantime, he and his coaching colleagues act as steadfast champions of the habits students must build in order to succeed at their coursework. Students regularly do homework at the tables that fill the Soccer Without Borders office, with help readily available. “He’s not only focused on making you a good soccer player,” said Abednego, who comes from Guatemala and aspires to be a lawyer. “He’s also focusing on making you a successful person for the future. He don’t care if you Omar described an occasion on which Mr. Gucciardi took a group of players to the home of a struggling teammate who had given up on school. “We went to talk to him, try and make him go back to finish high school, see how important it is to have a high school diploma in life,” he recalled. For another player, who was strong in both soccer and academics, the coach made sure he visited university programs and met the deadlines for college entrance exams. “Who does that for you?!” Omar exclaimed. “It’s amazing. And he treats equally everybody. [He says to us,] ‘Obviously you can apply too. You’re going to make it.’” Soccer Without Borders considers such support part of its core mission. Though players may struggle with academics or have issues with classroom behavior, “they are also very invested in soccer,” said Mr. Gucciardi. “To help them stay focused, we can leverage their participation on the team with some academic outcomes.” At such an intervention, student, family, and teachers typically confer together to agree on a plan and fair consequences —such as losing the right to play in games or at practices—if transgressions occur. In other cases, students who have dropped out maintain their connection with learning through soccer practice. One such student, now 21, left school in eleventh grade and “still comes all the time,” said Mr. Gucciardi. “He’s now finally decided he really wants to finish his GED, so he’s coming here to get help and support.” Such lasting bonds at once affirm and extend the culture of growth, opportunity, and empowerment the program seeks to create, the coach reflected. “We’re getting more intentional about that all the time.”

PHOTOS: LILI SHIDLOVSKI This article is an excerpt from WKCD's case study of Oakland International High School, one of five schools featured in Learning by Heart: Five American High Schools Where Social and Emotional Learning Are Core. It was conducted by WKCD's research arm, the Center for Youth Voice in Policy and Practice. DOWNLOAD THE FULL CASE STUDY, "A Place to Make My Own: Oakland International High School, Oakland, California" |

mically—they’re always there for me.”

mically—they’re always there for me.”