Learning by Heart: Giving Back at Quest Early College High School

by Barbara Cervone

|

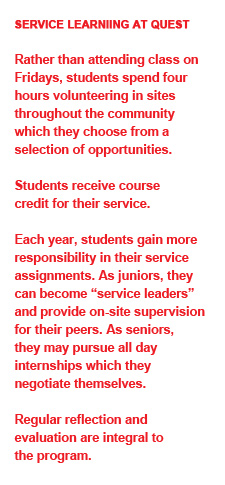

HUMBLE, TX—It’s a Friday morning in early October and instead of lugging backpacks to class, students at Quest Early College High School in Humble (pronounced “umble”), Texas are traveling light. As they do every Friday throughout the school year, the students jump into buses that will take them to the “service sites” where they will spend the next four hours. The school’s 300 plus students fan out across their suburban community, 25 miles north of downtown Houston —to elementary schools, a center for disabled young adults, an animal shelter, a hospital clinic, a nursing home, and more. At Jesse Jones Park, an oasis of small forests and fields a 20-minute drive from the school, one group, the “Green Team,” serves as environmental stewards. Another group tends to a nineteenth-century replica of a pioneer farm, built by Quest students several years ago. Clothed in britches and long skirts, they demonstrate the ways of early settlers to visiting groups of elementary school students. Black vest and trousers pulled tight around his narrow frame, Jason, a budding mathematician in school, sits on a stool surrounded by leatherworking tools and small pieces of animal skin. Pioneers would soften fresh skins by soaking them in water for six days, he explains, then use “brain paste” (brain innards mixed with water) to tan the hides. Across town, Missy is tutoring a third grader who just told her there was no point to school. “I’m just gonna go to work,” he says. After three years of serving as a teacher’s aide, Missy now wants to be a teacher. She takes the occasion to start a conversation with the child about grit. Jonathan, who has a brother with autism, works elbow to elbow with two disabled young adults at the Cambridge Center. As they roll out the dough for dog biscuits, he draws them into conversation about pet peeves. At the nearby Texas Medical Center, half a dozen students greet patients as they enter the large waiting room. The students offer water or coffee, ease the restlessness of young children waiting with an ill parent, and answer patients’ questions about what to expect. |

|

Making service core When the progressive Quest High School opened in 1995 with under 200 students, against a Texas landscape where large is sacred, its founders were making a bold wager: that bigger was not always better. They believed their new school would become a national model for best practices, while local skeptics, of which there many, bet the school would fade with the sunset.

One of the school’s founders, Kimberly Huseman, added a vision of her own: connecting students with local service opportunities to increase their engagement and motivation. She convinced her colleagues to set aside a full day in the Quest weekly schedule for students to serve as volunteers in the community. Almost two decades later, Quest students continue to spend their Fridays in service. When Quest became an early college high school four years ago, the tradition remained vital to the school’s mission. This commitment figured strongly in ASCD's selection of Quest as the 2011 winner of its prestigious “Whole Child Award.” “Service, it’s the heart and soul of Quest,” says eleventh grader Jonathan. “It’s all about giving back.” Students volunteer at an array of sites where Quest has built steady relationships. Like Missy, many find their place at one of the district’s elementary schools. They move quickly from helping a teacher with chores to working directly with groups of kids or individual students—teaching them to read, to speak English, to multiply, to persevere. Twelfth-graders may pursue an internship on their own, with the school’s backing. Or they can elect to become a service-learning leader assigned to a particular site; they alternate between observing classmates at work and providing feedback one week, then joining the action the next week. They receive special training for their observation duties, using a rubric developed for this purpose.

|

|

|

| Click on image to view audio slideshow |

Reflection and persistence As well as reflecting aloud on their service in their daily advisory groups (called “family” at Quest), students complete written reflections on their service at the end of each semester. They also evaluate themselves in four categories: attendance (e.g., consistent), attitude (e.g., exercised good judgment), learning process (e.g., showed initiative), performance (e.g., handled constructive criticism well). Their adult supervisor applies the same standards; service is a credit-bearing course. When a site placement does not gel (it happens), Quest’s service coordinator, Bobbie Rogina, steps in. Eschewing or being excused from service is not an option. Take the example of Celine (as we’ll call her) whose diffidence often made her hot to handle within the walls of Quest—and outside, too. When successive elementary school placements went sour, Rogina arranged for Celine to stack books at the public library while she searched for a placement that would not just accommodate Celine’s temperament but also challenge her. Rogina finally found a social worker at one of the district middle schools willing to take Celine under her wing—and where Celine has since flourished as an assistant. Celine met Bobbie Rogina’s persistence half way: she never gave up. Building relationships Service learning at Quest goes deeper than every student volunteering one day a week, four years running—as substantial as this is. It gains full force from the relationships it nourishes, say both students and staff. Vivianna applauds the annual day of service at high schools across the county, but wondered what students got from this “one-off” experience.

After four years working in two elementary schools, Missy looks back.

|

|

Social and emotional learning Importantly, service at Quest holds value in its own right. Though many schools strive to link learning to the academic curriculum, here the ties to social and emotional learning matter most. “It creates a better whole child,” Bobbie Rogina states simply. “It’s the little stone that creates a huge ripple.” Looking back on their service experience, several seniors who act as service learning leaders made a list of what they had learned: to relate to people of different ages and backgrounds, to communicate better one-on-one and publicly, to take initiative and assume responsibility, to show patience, to reach out without being asked, to think ahead. Most of all, students will tell you, they feel they are making a difference through their service work. For adolescents—an age where idealism and justice compete with self-absorption—the belief that their contributions matter goes a long way to making them feel valued, themselves. Youth grow in important ways when adults in the community invite and salute their contributions, research suggests. The 40 developmental assets identified by the Search Institute as critical to youth ages twelve to eighteen include promoting equality and reducing hunger and poverty, helping others, acting on convictions, and a sense of purpose. “When I came to Quest, I saw Fridays as a day I didn’t have to go to class and could, you know, knock off,” Jonathan admits. “Now I don’t just want to make an impact in my community, but all around the world if I can.” Phillip picks up the beat: “I came here figuring I’d give it a year, then probably go back to regular high school. Now I can’t imagine doing high school without service.”

This article is an excerpt from WKCD's case study of Quest Early College High School, one of five schools featured in Learning by Heart: Five American High Schools Where Social and Emotional Learning Are Core. It was conducted by WKCD's research arm, the Center for Youth Voice in Policy and Practice. DOWNLOAD THE FULL CASE STUDY, "I Belong Here: Quest Early College High School, Humble, Texas"

|

It wasn’t just size that set Quest apart. Everything about the school was different. Classes were interdisciplinary, teachers “facilitated” rather than lectured, and mastery, not grades, tracked learning. The Quest “creed” had just two dicta: respect yourself and others in word and deed, and keep a clean and safe environment.

It wasn’t just size that set Quest apart. Everything about the school was different. Classes were interdisciplinary, teachers “facilitated” rather than lectured, and mastery, not grades, tracked learning. The Quest “creed” had just two dicta: respect yourself and others in word and deed, and keep a clean and safe environment.