CLOSE-UP

Learning by Heart: Developing Student Agency at Springfield Renaissance School

by Kathleen Cushman ____

|

In a city where 40 percent of children live in poverty, Springfield Renaissance School in Springfiled, MA, a magnet middle and high school, sets a high bar: college acceptance acceptance for everyone. Last June's graduating class, the first in the school's six-year history, hit the mark: one hundred percent acceptance. |

|

|

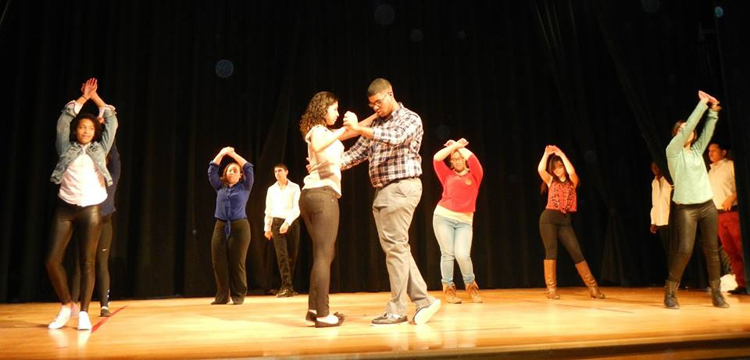

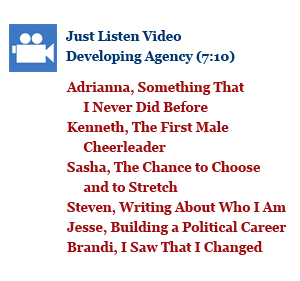

Finding a voice Bridget Camara teaches the drama course that all Renaissance students take for a semester in grades 9, 10, and 12. (Eleventh graders must take a semester of health instead.) Its chief point, she said, is not to learn to act but rather “to find your voice.” Starting with scenes from their own lives, Ms. Camara aims to help even the most introverted of youth “at least get up there and say something,” she said. For the extroverts, “it’s about trying to learn to listen to other people and try to have some self-control,” she noted. Steven wished he had even more opportunities for creative expression in his tenth-grade academic classes. Still, he had recently brought his passion for hip hop into an English class writing assignment called “I Am.” It took him five hours to write those one hundred lines, he said. “There’s a lot of things that people don’t know about me from school—even though they have been with me since sixth grade—that I’d like them to finally realize who I really am. So I took the time to, you know, make a big plot. Like, “This is who I am. This is what I want people to know about me.” Griffin, an eighth grader, had also started to experiment with possible selves. “Some students feel very comfortable talking about their real self,” he said. “But students like me, I put on a very different mask when I’m at school.” Though others may consider him happy and outgoing, he declared, “I’m not like that, other places. I’m very quiet. I’m reserved, and I don’t, I don’t like to stand out.” In Griffin’s view, his school “gives you a place to not be something you’re not, but to be something better than you are . . . without being fake, essentially.” During a “Spirit Week” the previous year, he tried dressing for school completely in orange. “I won Spirit King that week,” he said with satisfaction. Pushing past fear Many other students spoke of pivotal school experiences that supported their search for identity. To a striking extent, these situations had also persuaded them that their own effort, not talent, was increasing their ability and competence. By the end of tenth grade, for example, Luis saw himself as someone who could “take on challenges that not everyone will take.” He said, “Courage means to confront your fears . . . [to] still keep it going even though it’s hard. And that’s what I’m basically known for here at my school.” Despite his apprehension about sports, Luis had tried out for the swim team to fulfill the physical challenge requirement for his Passage Portfolio. Success at that gave him the confidence to try baseball later in the year. “I can look at myself in the mirror now,” he said with satisfa When her crew advisory planned a class meeting for the whole ninth grade, Adrianna also felt her courage tested. “It’s hard for me to get up on stage and talk to a group of 100 students, because it’s something that I never did before,” she said. But she felt that “I need to take part in this. I need to make sure this goes well with my crew. I was kind of like one of the main people planning. . . . I need to work hard on it.” As she approached high school graduation, Brandi too reflected on her development from a hesitant sixth grader into a leader. “Going through seventh and eighth grade, I was still trying to come out of my shyness,” she said. Then the school’s annual Outward Bound wilderness expedition for rising ninth graders challenged her to try a different role (“like leading my group through the forest at one o’clock in the morning, just to get to our next campsite”). Brandi considers that experience one of the hardest in her life. She also believes it made her stronger. “I kinda call my transformation from sixth to twelfth grade like a butterfly kind of like coming out of its cocoon,” she said. “Like getting ready to fly and going on to college and having to spread my wings there.” |

|

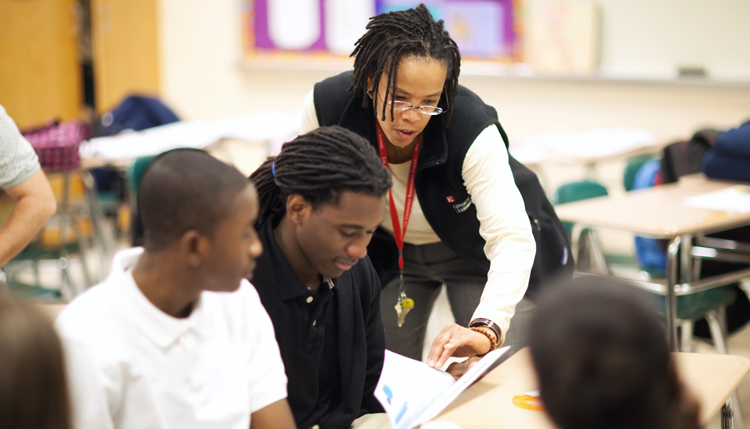

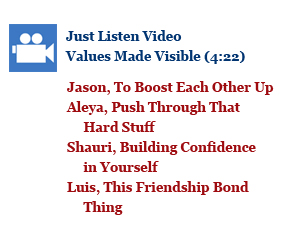

Reaching toward success Advancing from the middle grades through high school, Renaissance students have steady support in coping with their emotions and regulating their actions. They gain ever more practice in monitoring their own learning processes: setting individual goals, evaluating their own progress, posing problems and designing ways to solve them. They exert more autonomy, making choices for themselves about what to reach for next. As they grow to believe that success is possible and within their control, they are developing the sense of agency that leads to a productive and satisfying life. In eighth grade, Ajeya aspired to be a coroner like those she saw on “L.A. Law.” She pushed herself to do better in science classes, where she had often struggled. “I feel like I’m getting better as I study more and I do more work or I ask peers for help,” she said. “I wanna push myself to be better.” In a seventh-grade crew session on looking ahead to college, she discovered that New York University offered “a really big forensic science major, where coroners would come in, too.” Now she has put NYU on her dream list of colleges, and is also researching other institutions with forensics programs. “We do put a lot of emphasis on planning here,” her classmate Griffin commented. His teachers “never let us just jump into work,” he said. “It’s always, ‘You need to plan out what steps you’re going to do. Make sure you have what you need to do to fill out those steps. And then complete the steps.’” After his science class studied the engineering design process, teachers of other subjects also adopted it—“because it fits!” Griffin explained. “Finding out the question, finding out possible solutions, doing the possible solutions, picking out the best one. And then redoing the process again to find the best answer until you find the best answer.” Growing into something bigger In their descriptions of school, all these students offer important evidence that social and emotional learning both informs and supports their academic learning at Springfield Renaissance School. Not just the design of the school but the everyday decisions and actions of its staff situate students at the center, and in doing so they illustrate the theory of action that underlies all five of our case studies: When students feel a sense of belonging in a school and its classrooms, when they beli In May of his ninth-grade year, Griffin could have been speaking for many of his schoolmates as he reflected that his confidence, determination, and perseverance had all increased during his time at Renaissance. “It’s you talking, and you need to get comfortable with that,” he declared. “And I feel like [here] is where I learned it from. It allows you to grow into something bigger than yourself.”

This article is an excerpt from WKCD's full case study of Springfield Renaissance School, one of five schools featured in Learning by Heart: Five American High Schools Where Social and Emotional Learning Are Core. It was conducted by WKCD's research arm, the Center for Youth Voice in Policy and Practice. DOWNLOAD THE FULL CASE STUDY, "A System of Working Parts: Springfield Renaissance School, Springfield, Massachusetts" |

ve to limit yourself.”

ve to limit yourself.” ction, “and definitely say who am I as a person.”

ction, “and definitely say who am I as a person.” eve that their efforts will increase their ability and competence, when they believe success is possible and within their control, and when they value what they are learning, then they are much more likely to persist at academic tasks despite setbacks and to demonstrate the kinds of social, emotional, and academic behaviors that lead to a productive and satisfying life.

eve that their efforts will increase their ability and competence, when they believe success is possible and within their control, and when they value what they are learning, then they are much more likely to persist at academic tasks despite setbacks and to demonstrate the kinds of social, emotional, and academic behaviors that lead to a productive and satisfying life.