How Youth Learn: A Portfolio to Inform and Inspire Educators, Students, Parents & More

| Adolescent Development: Research Highlights | SHARE | |

| SEE ALSO: Conditions of Learning |Mind, Brain & Education |Teenage Brain | Mindsets Motivation & Mastery | Social & Emotional Learning |

Are Romeo and Juliet the quintessential adolescents?

|

|

|

On the yes side, they were rebelling against family traditions, in the throes of first love, prone to drama, and engaged in violentand risky behavior. But the truth is that there was no such thing as adolescence in Shakespeare’s time (the 16th century). Young people the ages of Romeo and Juliet (around 13) were adults in the eyes of society—even though they were probably pubescent.

Paradoxically, puberty came later in eras past while departure from parental supervision came earlier than it does today.

Since the mid-1800s, puberty—the advent of sexual maturation and the starting point of adolescence—has inched back one year for every 25 years elapsed. It now occurs on average six years earlier than it did in 1850—age 11 or 12 for girls, age 12 or 13 for boys. Today adolescents make up 17 percent of the U.S. population, and the scientific study of their development toward adulthood has also increased in magnitude.

Changing scientific perspectives

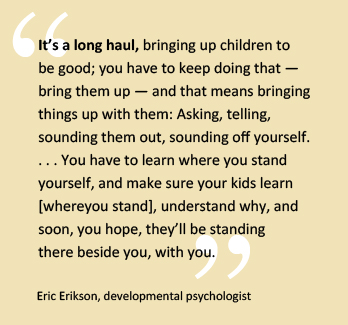

Through the mid-20th century, scientists saw adolescence from a deficit perspective: a process grounded in biology, in which a child developed from a primitive to a civilized state (G. Stanley Hall, 1904, Anna Freud, 1969). The psychologist Erik Erikson (1950, 1959, 1968) described it as a series of stages that began with an inherited maturational map and progressed through a crisis of identity. Others, like Piaget (e.g. 1970), treated nature and nurture as separate, not integrated, parts of the developmental process.

By the 21st century, however, evidence emerged supporting a much more dynamic and integrative model of adolescent development, which also amplified the understanding of human development across the life span (Steinberg & Lerner, 2004). In this light, young people’s biological development and increasing brain capacity between 10 and 20 years of age was seen to influence the multilayered and changing contexts of their lives, and vice versa. Family, peers, school, and community all played parts in this dynamic system (e.g., Collins et al., 2000; Gottlieb et al., 2006)—and that had enormous implications for educators.

We now know that adolescents are experiencing changes in the way they think, not only about abstract concepts but also about themselves and their potential. Teenage youth can think about their own thinking (“metacognition”) and, as their social perspective develops, they can consider how that thinking relates to the views of others. Within the ecological contexts of their families, peers, social groups, schools, and neighborhoods, they are beginning to develop and negotiate “identity orientations” with respect to their gender and sexuality, race and ethnicity, abilities or disabilities. Themes of attachment and autonomy (McElhaney et al., 2001; Holmbeck, 1996), risk and resilience (Coleman & Hagel, 2007) fairness and morality (Damon, 1988; Eisenberg et al., 2011) weave throughout the adolescent years.

How adults can make a difference to adolescent development

In and after school, at work, and at home, the adults with whom youth interact play important roles in their positive development. When we listen well to young people and appreciate their perspectives, we build the trusting relationships that lead to their resilience and growing accomplishment.

School serves as the primary environment in which adolescents develop relationships with peers as well as key cognitive skills. For some youth, it also provides safety and stability. Some of the same qualities that characterize families of adolescents who do well—a strong sense of attachment, bonding, and belonging, and a feeling of being cared about—also characterize adolescents’ positive relationships with their teachers and their schools (APA 2002).

Whatever their role, adults make a measurable difference to the healthy development of youth, research shows. The following suggestions are adapted from the American Psychological Association’s 2002 reference booklet for professionals, Developing Adolescents:

- Give young people opportunities to learn in ways that emphasize different types of abilities (Sternberg, 1996). Encourage them to step outside gender stereotypes regarding their academic competencies (Eccles, Barber, Jozefowicz et al., 1999). Directly reinforce adolescents’ growing competencies by simply noticing and commenting on them during routine contacts (Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & Eye, 1998).

- Show fairness in your interactions with youth. Identify and discuss issues involving fairness and morality, in a positive and sensitive atmosphere. Encourage adolescents to express themselves, ask questions, clarify their values, and evaluate their reasoning (Eisenberg, Carlo, Murphy, & Van Court, 1995; Santilli & Hudson, 1992).

- Model altruistic and caring behavior toward others and help youth take the perspective of others in conversations. Help them understand the value of volunteering and direct them toward valuable volunteer experiences.

- Adolescence may be the first time that youth consciously confront and reflect upon their ethnicity (Spencer & Dornbusch, 1990). About a third of adolescents belong to racial or ethnic minorities, which may involve both positive and negative experiences. Help all students understand the great diversity within ethnic and racial classifications, empathize with different groups of immigrants, and emotionally grasp the negative consequences of prejudice (Aronson, 20000. Help ethnic minority youth discuss and practice aspects of their own ethnic identity, make sense of the discrimination they may face, and build the confidence and skills necessary to overcome these obstacles (Boyd-Franklin & Franklin, 2000; Oyserman, Gant, & Ager, 1995; Phinney, Cantu, & Kurtz, 1997).

- Create a supportive environment in which lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning adolescents can negotiate the developmental task of realizing and incorporating their sexual orientation in an often hostile environment (Fontaine & Hammond, 1996; Ryan & Futterman, 1998; Savin-Williams, 1998). Provide safe ways for them to express themselves and build alliances.

- Help youth develop “emotional intelligence.” Being aware of and able to label their feelings helps them identify options and do something constructive about them (Goleman, 1994). Adolescents who lack social skills may be rejected by their peers, and this rejection can have serious negative effects, such as delinquency, drug abuse, dropping out of school, and aggression (Asher & Coie, 1990; Olweus, 1996). Informal discussions about how to initiate conversations with peers, give genuine compliments, be a good listener, share private information appropriately, and keep confidences can go a long way toward enhancing social skills.

- Intense desire to belong to a particular group can influence young adolescents to go along with activities in which they would otherwise not engage (Micucci, 1998; Santrock, 2001). Help them withstand peer pressure and find alternative “cool enough” groups that will accept them if the group with which the adolescent seeks to belong is undesirable (or even dangerous).

- Adolescent risk-taking has many positive aspects, and most adolescents will take some risks. Talk comfortably with adolescents about decision-making in sensitive areas such as sex, drugs and alcohol, online activity, and other safety concerns. Help them practice weighing the dangers and benefits of a particular situation, considering their own strengths and weaknesses that may affect decision making, and then make the best decisions possible (Ponton, 1997).

- Resilience can be seen as a function of developmental experiences that are grounded in a community context (Debold et al., 1999). Create and support strong afterschool opportunities that engage youth as early in adolescence as possible, involve at least one adult who is personally attached to each adolescent in a meaningful way, involve parents and peers, are located in schools, and address the varied needs of youth (Lerner & Galambos, 1998).

- Offer to confer with youth in making important decisions about such things as attending college, finding a job, or handling finances (Eccles, Midgley, Wigfield et al., 1993). Help them expand their range of options so they can consider multiple choices.